- Stay Connected

The Arab-Turkish penetration and the rivalries in the Horn of Africa

The Economist has recently written about the new exchange for Africa focusing mainly on Chinese expansion in sub-Saharan Africa. But there is another expansion that particularly affects the Horn of Africa, whose renewed strategic value is paradoxically due in large part to destabilizing phenomena such as terrorism, international piracy and insurgency, which push many to take actions aimed at safeguarding commercial interests , energetic and political-diplomatic from factors of growing insecurity.

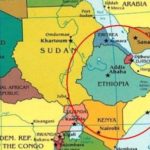

The current dynamics in the Horn of Africa reflect the spill over of the consolidated rivalry between the Saudi Arabian and Turkish-Qatari front, exacerbating pre-existing local and international divisions and raising the question of how much the states involved represent a stabilizing force in this piece of Africa.

The Gulf countries have considered at least the African territories of the Red Sea since the 1990s as a strategic rear-view to be consolidated and the governments of their respective states as potential allies, linked by a historical and cultural heritage at least partly shared but also motivated by opportunism strategic.

The double axis composed of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates on the one hand and by Turkey and Qatar on the other is the absolute protagonist of this unprecedented race to control ports and landings. Common to all the actors is the interest in consolidating or strengthening control over the Bab-el-Mandeb strait, a fundamental trade route that connects the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Sea through which 8 percent of the oil transits worldwide and where Saudi oil tankers are regularly attacked by pro-Iranian insurgents.

In the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea, the Gulf powers export intraregional rivalries in a vulnerable context already characterized by a combination of political-energy-security but also climate-humanitarian-environmental dynamics of international importance.

To border disputes not completely resolved (Ethiopia-Somalia and Sudan-Ethiopia), interethnic conflicts and rebel groups is added the nascent internal competition for energy resources between Somalia (the Puntland region has unexplored oil reserves), Ethiopia ( where the first extractions took place only a few months ago in the Ogaden region, also rich in gas fields), and Sudan, a traditional exporter of oil in the Horn.

The OCHA ( United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs ) estimates that 27 million people are currently in a food emergency situation in the region; 11 million would be internally displaced, a part of which had to leave their homes due to the floods that hit the region during 2018, and 4.5 million refugees. According to IOM, only in 2018 would have been 400,000 migrants from Eritrea, Somalia and Djibouti to Europe.

The multi-level game sees Saudi Arabia and the Emirates aiming to contain Iran, and Qatar with Turkey will fight the Saudi influence and the emiratin with all its strength.

The Gulf states have extended security interests in the region, which include both the economic and the military security dimension. This is confirmed by the huge investments in logistic infrastructures and installations made with the aim of protecting national and sub-regional interests from exogenous or endogenous threats, but also to secure a privileged outpost on the war in Yemen.

This need has become urgent since June 2017, when rivalries on the Arabian peninsula reached their climax when Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain interrupted diplomatic and commercial relations with the Qatar by imposing an embargo on the country, which in January last year also withdrew from the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. Since the outbreak of the crisis, both factions have intensified their relations with East African countries by attempting to forge alliances with their African governments through economic partnerships and military agreements.

The competition between the Gulf states does not manifest itself in a simple export of tensions but goes so far as to reshape the alliances and the geopolitics of the region. This would take place at the same time through a mix of inter-state pacification processes in the Horn of Africa, of which Middle Eastern states would become promoters, and through an increasingly aggressive penetration in the internal affairs of some states that in some cases has exacerbated the pre-existing internal tensions, considered secondary to the interest in acquiring greater political-diplomatic influence on the Red Sea region.

For example, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have contributed to the normalization of relations between Eritrea and Ethiopia (the peace agreement was signed in September in Jeddah), to promote dialogue between Eritrea and Djibouti regarding the age-old question of Dumeira, and also to lighten the tensions between Ethiopia and Egypt for the construction of the “Ethiopian Renaissance” dam, while they created a real proxy war in Somalia, where intra-Arab tensions between the Arab Emirates and Qatar rekindled the spirits among Mogadishu and some federal governments including the self-declared state of Somaliland.

The regional distension in the Horn creates unprecedented opportunities for external actors that the Gulf countries – but not only – do not want to miss: from development aid, the need for infrastructure and financial support, the market is not lacking.

New opportunities also emerge from the underground market. As a recent report by EXX Africa notes , the normalization of relations between Eritrea and Ethiopia could have as a side effect a reorientation of the routes of illicit arms trafficking between the Arabian peninsula and the Horn of Africa, where the activities related to this traffic would be on the rise in Djibouti, whose government supports armed groups in northern Somalia. Military material destined for forces not aligned with the central government and coming from the Emirates had been found in Somalia by the United Nations group of experts already in 2015.

Specifically, the division of influence takes place through the installation of permanent military bases and the creation of port logistics hubs along the entire Red Sea coast. There are as many as 8 countries that currently have a military base or installation in the Horn of Africa: France, the United States, Japan, Italy, the United Arab Emirates, China, Turkey and Qatar.

As Giuseppe Dentice of ISPI notes, Saudi Arabia is consolidating its presence through maritime infrastructures “that aim at building a strategy aimed at retaining allies through financially advantageous partnerships and agreements”.

The pieces of this strategy are clear. In 2016 the kingdom had repossessed the islands of Sanafir and Tiran, whose control offers access to the ports of Eilat in Israel and of Aqaba in Jordan, and therefore full access to the Red Sea. The NEOM civil-type infrastructure project, launched at the end of 2017, provides for the creation of a highly technological futuristic city and the first free zone in the world that should arise between Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Jordan and aims to establish the area as a global hub linking Asia, Europe and Africa.

The Saudi kingdom is currently in talks for the construction of a base in Djibouti, a country that already hosts military installations from as many as five countries, including an Italian one, inaugurated in 2013. Motivated above all by the need to contain Iran and counter the influence of Qatar, in the Horn of Africa Saudi Arabia has invested particularly in the agricultural and manufacturing sector. Furthermore, the Saudi armed forces are already present in Assab in Eritrea, where in 2016 a military base was built to support the war effort in Yemen.

And it is precisely the United Arab Emirates that have become the major protagonists in the African sub-region, considered “the western side of its security front”. In Somaliland they are building a naval base that will open by June, which has caused the hassles of Mogadishu.

In May last year, Abu Dhabi also unilaterally decided to deploy military forces on the island of Socotra in Yemen (where it had already tried to convince the inhabitants to vote for a referendum for self-determination), then withdrawn because of protests of the local population against the deployment of 4 military jets and more than 100 Emirates troops .

The Emirates have been present militarily in both Assab and Berbera since 2015 and have provided significant assistance to Puntland’s maritime police forces to combat piracy and Islamist groups. In Jubbaland they are discussing the development of the port of Kismayo, while in Somaliland the Emirates are also planning to train the coast guard.

The strategy implemented by the Emirates is to “fill the available space before others do”, as reported by the International Crisis Group. This also happens through the construction or modernization of infrastructures, in particular energy: for some months the Emirates have been building an oil pipeline that would connect the port of Assab with Addis Ababa in Ethiopia.

ReaMore