- Stay Connected

Opinion: Nobel Peace Prize for Abiy Ahmed a misguided decision

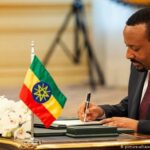

The Ethiopian laureate is surely a reformer, but he predominantly garners recognition beyond his country’s borders. Despite the Nobel committee’s well-meaning intentions, it is the wrong choice, writes Ludger Schadomsky.

Despite a number of somewhat questionable recipients — such as former US President Barack Obama, or the European Union — the Nobel Peace Prize continues to carry considerable symbolic meaning. For precisely this reason, awarding it to the young reformer hailing from Addis Ababa despite the stalled progress on his peace initiative is also the wrong choice.

Peace with Eritrea? Or dead silence?

Abiy Ahmed took office in April 2018, becoming PM of Africa’s second-most populous nation, which also holds tremendous geostrategic importance. Let there be no misunderstanding: Since taking office he has pushed for reforms , the importance of which are impossible to overestimate. He unlocked the torture chambers and took the muzzle away from the media. All of this deserves unqualified respect, even if, in the meantime, the initial euphoria has waned a little.

Of course, Abiy was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to a lesser extent because of his “important reforms” in the domestic domain but explicitly because of his efforts regarding a lasting peace with Ethiopia’s archrival Eritrea — the two countries were involved in a border war from 1998 to 2000, which led to heavy losses on both sides. And wasn’t it a very moving scene indeed in July 2018 when, Abiy made it possible for family members separated for two decades to embrace each other again?

Those peace efforts, however, have come to a standstill; they may even have stopped completely. True, family members and businesspeople are now able to commute via 50-minute flights between the two respective capitals, Addis Ababa and Asmara. But this is the privilege of only a small elite. Border crossings such as Zalambessa, which are much more important when it comes to public transportation and movement of goods and which were opened with a lot of fanfare, have all been closed again in the meantime — at Eritrea’s instigation, Ethiopia was quick to point out. The initial shuttle diplomacy pursued by Abiy and Eritrea’s autocratic ruler Isaias Afewerki has come to a halt. The Eritrean embassy in Addis Ababa continues to remain boarded up while grandiose business contracts that were signed have never been brought to life. By now, both countries have rather resorted to forging unholy strategic alliances with countries located beyond the Red Sea, in accordance with that age-old motto that Horn of Africa nations ascribe to: “The enemy of my enemy is my friend.”

Will the Prize eventually endanger peace efforts?

So Abiy has received the most prestigious peace prize for a peace that exists, predominantly, only on paper. Worse still: the award could, eventually, even torpedo those peace efforts, if the Eritrean leadership felt put under pressure to an even greater extent than before. The grumpy autocrat from Asmara, who ruthlessly keeps his own people in chains so he can remain in power, is unlikely to enjoy being snubbed under the eyes of the world by a charismatic politician half his age.

Everybody’s darling on the world stage, vociferous criticism at home

On the domestic politics level, the award provides ammunition to those critics who have slammed the young and dynamic Prime Minister’s approach to politics as detached from reality and insubstantial. In an Ethiopia that is socially conservative to the core, the prime minister’s PR-guided demeanor — accompanied by an unprecedented “Abiymania” — has sparked some resentful allegations that the former secret service agent is engaged in questionable activities benefitting his ethnic group, the Oromo.

But it’s not just his fellow Ethiopians who view him with criticism — his development policy partners also view with concern the young PM’s personality cult and style of government – which is sometimes rather erratic and lacking in communication.

Is Abiy’s reconciliation policy sustainable?

Unfortunately, Abiy’s award is evocative of the one given in 2000 to former South Korean President Kim Dae-jung, who had been in office for only two years before he received the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to reunite the divided Korean nation. North and South Korea, however, are divided to this day.

Currently, there’s a lot of talk about “Medemer,” Abiy’s programmatic policy of reconciliation. One day before he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Abiy had invited heads of state and government from all over the region to take part in a huge “Medemer” celebration. Sudan, Somalia and Uganda all sent their representatives while only one distinguished guest was absent — Eritrean President Afewerki, Abiy’s partner in the “reconciliation” process. It is likely that the award of the Nobel Peace Prize has raised the bar for Abiy instead of lowering it.