- Stay Connected

Ethiopia and Kenya are struggling to manage debt for their Chinese-built railways

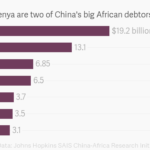

In the wake of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Forum in Beijing six weeks ago, Ethiopia gained another Chinese debt-concession. China’s second-largest African borrower and prominent BRI partner in infrastructure finance also received a cancellation on all interest-free loans up to the end of 2018. This was on top of previous renegotiated extensions of major commercial railway loans agreed earlier in 2018.

These concessions highlight the continuing debt-struggles that governments have in taking on Chinese large infrastructure projects. But they also demonstrate the advantages and flexibility, that African governments can gain in working with China—if they can leverage it.

Ethiopia’s railway projects have been an instructive case of both the benefits and pitfalls of Chinese finance. It has been over a year since the Chinese-built and financed Addis-Djibouti standard gauge railway (SGR) opened to commercial service in January 2018. A flagship project of China’s Belt and Road Initiative in the Horn of Africa, and constructed in parallel with Kenya’s showy Chinese-built SGR, the project was Ethiopia’s first railway since a century ago (another urban-rail project, the Addis light-rail transit (LRT) was completed earlier in 2015), as well as being the first fully-electrified line in Africa.

Costing nearly $4.5 billion, the SGR was partly financed through $2.5 billion in commercial loans from China Eximbank, according to figures from SAIS-CARI with further loan packages dedicated to transmission lines and the procurement of rolling stock and locomotives. Part of China’s wider ‘export-supply chain’ strategy, the railway uses a package of Chinese trains, Chinese construction companies, Chinese standards and specifications—and is currently operated under a six-year contract by a joint venture of the two Chinese contractors, CREC and CCECC, who built it.

As part of a wider nine-line railway network plan under the Ethiopian Railway Corporation (ERC), the line cuts travel time from the capital Addis Ababa to Djibouti from two days by road to 12 hours. Passing several industrial zone clusters in Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa, it also serves the government’s wider export-led industrialization strategy, through the strategy of “transit-oriented development”, writ on a national scale.

But despite these lofty ambitions, the project has been afflicted by technical and financial challenges, calling into question the wisdom of relying on Chinese technology, as well as debt-financing, for major infrastructure. Despite the line’s completion in 2016, delays in the construction of the transmission network held up the railway’s commission, and problems with power outages and technical issues of over-voltage have continue to plague the line in the first year of operation.

Other social challenges have also emerged out of railway design choices: the decision to not erect fencing along rural tracts of the railway (both for cost-saving purposes and a concern to not divide pastoral communities) has led to the regular phenomenon of collisions between the train and livestock, resulting in conflicts over compensation; the railway become a target for blockades in regional ethnic tensions in the last year, leading several instances of disruption to service.

On an economic front, actual uptake of the railway by the industrial zones it was intended to serve remains low—even after a year, the vast majority of the railway’s freight cargo is made up of imports, not exports. Integration with export and industrial zones is low, as the main trunk line does not connect to individual industrial zones, creating significant last-mile shipping and logistics for firms, particularly at port connections. Most exporters continue to use road transport, despite the higher time and financial cost, due to its greater flexibility and reliability compared to the train’s twice-daily schedule.

This is a major problem for the railway’s economic prospects. Few passenger-based rail systems in the world are profitable; in developing countries, most railways connect to mines: one of the few bulk goods that can generate returns for such capital-intensive transport.

China also bears these costs. State insurer Sinosure publicly commented on $1 billion in losses written off for the project, and Eximbank has halted previously-discussed funding for the country’s second line, the section from Weldiya to Mekele. Though contracted to another Chinese SOE, CCCC, Ethiopia faces little prospect of further loan finance from China, until the first railway can show demonstrable success.

Further financial challenges afflict the projects, along with Ethiopia’s growing debt burden. A long-term foreign exchange shortage, worsened by poor export performance, has challenged Ethiopia’s ability to repay many of the loans that financed these projects. Repayments on the principal for the Chine se railway loan began in 2017, before the line was even operational. As of the beginning of 2019, the ERC was not only behind in its loan repayments to China, but also unable to front the remainder of the management fees for the Chinese companies operating the railway.

se railway loan began in 2017, before the line was even operational. As of the beginning of 2019, the ERC was not only behind in its loan repayments to China, but also unable to front the remainder of the management fees for the Chinese companies operating the railway.

In late 2018, Ethiopia negotiated with Beijing to restructure of the Eximbank loan terms, extending the repayment period from 15 to 30 years.

China’s railway loan concessions to the Ethiopian government also contrast to the other debt-financed railway project the government is constructing: under Turkish contractor Yapi Merkezi, Ethiopia’s second railway line from Awash to Weldiya is still under construction, financed by a consortium of mostly European lenders including Turkish Eximbank and led by Credit Suisse. Despite its delayed Chinese debt repayments, Ethiopia has reportedly never missed a payment to its European creditors, where the penalties to future access to credit are harder.

In this, China’s deep and strategically-tied pocketbook has been a big advantage, allowing Ethiopia to juggle its external obligations and leverage Chinese flexibility where it can. Ethiopia’s renegotiation and rollover of debt indicates that this BRI project is unlikely to have a Hanbantota-esque Chinese takeover. In contrast, Kenya’s Mombasa-Nairobi railway—another Chinese-designed and built SGR which has seen similar concerns over debt-burdens—but curiously has not received similar concessions from China—and has struggled to gain further funding from China for its expansion. Longer-term challenges remain in the national railway’s development and success. Financial concessions buy Ethiopia more time, but the government still faces an ongoing challenge of capacity building for the eventual handover of railway operations to Ethiopian ownership. China has supported through training exchanges in the form of student exchanges and in the construction of a new railway academy dedicated to vocational staff training—and the case of the light rail transit shows some early success: after three years, daily operation has been entirely localized to Ethiopian staff.

However, the Addis-Djibouti SGR has seen more missed opportunities: the very fact that operations and maintenance were awarded to construction contractors with no actual railway operations experience is indicative of the failure of adequate capacity building during construction. The government too, has learned from this, pressuring Turkish contractors Yapi Merkezi in the Awash-Weldiya rail project much harder on capacity building for ERC engineers and construction staff.

Under Ethiopian premier Abiy, the Horn of Africa country is also learning and adapting in other ways in managing its external partners, increasingly looking to encourage private sector finance and public private partnerships to finance future railway developments.

Outside of railway, though, China remains a viable partner: the recent signing of a new power project still demonstrates the considerable sway that China holds as a financier where other international sources of credit remain scarce. But both sides have been burned: while the strategic discourse of the Belt and Road mean that the SGR will not be abandoned, both lender and borrower now show greater caution in the infrastructure they pour money into.